Folk and Baroque: Tim and Jeremy's Trip to Scotland

Fiddlers! Your pegs in temper fix,

And rosin well your fiddlesticks,

But banish vile Italian tricks,

From out your quorum,

Nor fortes with pianos mix,

Give us Tulloch Gorum!

~Excerpt from “The Daft Days” by Robert Fergusson, 1772 (tr. from Lallans to English)

Fiddle music tends to straddle worlds. Many players emphasize the community inherent in folk music, valuing a good night of tunes with friends at the pub over a technically-brilliant performance…yet at the same time there’s been an active competition scene in Britain, America, and elsewhere since at least the early 18th century. Scotland is no exception; in fact the great patriarch of Scottish fiddling, Niel Gow (1727-1807), first achieved fame by winning an open fiddle competition in Perth in 1745.

This legacy continues to the present day. Fittingly, the most prestigious Scottish fiddle competition in the world—the Glenfiddich Fiddle Championship—takes place in the nearby town of Blair Atholl, in the very castle where Niel Gow performed for six decades, with competitors sharing a stage with a portrait of Auld Niel himself and one of his alleged fiddles. Eight players are invited from around the world to be cheered on by hundreds of audience members, judged silently by Niel’s oil-painted eyes, and ranked by three adjudicators.

I was honored to be invited for the 2015 competition (earning the spot by winning the 2014 US National Scottish Fiddling Championship) and was delighted that my friend and co-conspirator Jeremy Ward agreed to come along as my accompanist. Not one to waste a trip, I stretched it to three weeks of musical shenaniganry, with Jeremy coming along for the middle week.

At the competition, however, I made some decisions that further illustrate the world-straddling of fiddle music. Fiddlers constantly balance the desire to respect the traditional background of their music yet innovate to find their own voice and their own style. When the primary means of tradition is oral, this usually happens by learning the “traditional” way from one’s elders when young, evolving it to match the taste of the player and the aesthetics of the time, and then passing on this subtly-different style to the next generation.

The Glenfiddich is famous for being a “traditional” competition, and indeed, most players sounded like the musical grandchild or great-grandchild of fiddling great James Scott Skinner (1843-1927), respecting his way of playing yet beginning to add nice touches of their own.

I chose a different tack. Like most folk genres, Scottish fiddling has a strong oral tradition. However, it’s unique in also having an excellent written tradition. The Scottish Reformation led to very high literacy rates in Scotland, which led to a booming printing industry, which led to sheet music production that was beginning to get off the ground as early as 1680 and was in full swing by the mid 18th century. Scottish violinists of the time did their own straddling—this time between the dance and song music native to Scotland and the chamber music of the Continent (especially Italy). A truly dizzying amount of printed information exists about the music of the period, and it’s finally beginning to get the academic treatment and public performance it deserves.

So rather than play the traditional music of 2015, I made the choice to play the traditional music of ca. 1795. This was a first at the Glenfiddich, as was my choice to use a Baroque violin instead of a modern one, my choice to work a minuet into one of my sets of tunes, and my choice to invite Jeremy to play with me on his violone (every other accompanist in the history of the competition used a piano). But more important than changes of equipment or repertoire or pitch (we were also the first to play at A=415hz instead of A=440hz) was the change of style. Rather than the 20th century focus on tone production, technical fireworks, and drive, we adopted the more Scottish-Baroque ideals of careful note-shaping, lilt, and space (Jeremy explained the difference as one of left-hand expression (focusing on the fingering) vs. right-hand expression (focusing on bowing)). And rather than fully committing to the modern formality of the competition (there was even a sign prohibiting smoking, photography, and foot-tapping) we took a more laid-back approach and tried to communicate the joviality of the music with our bodies, faces, and gestures—not just the notes coming out of our instruments.

The most striking result was the audience response. Regrettably, Baroque music often engenders a stereotype of stuffy music and stuffy players focused more on historical research and elegant frappery than truly moving performances. But instead of politely golf clapping, the audience carried on and made more noise with hands and voice than I thought possible. A great moment! And I was especially thrilled to talk to a handful of them after the competition. Some were true musical or historical experts, and I had wonderful discussions with them about the fine details of the performance. But others just wanted to hear a braw choon or twa and appreciated the period performance for its musicality and entertainment value, not its historicity or its academic credentials. Now more than ever I’m convinced that my own solution to reconciling the constraints of tradition and the desire for innovation is simply to help resurrect the Scottish music of the 18th century Lowlands. Not to “banish vile Italian tricks”, as Mr. Fergusson pleaded for in the above poem (and as indeed happened shortly after his untimely death at 24), but to be one of the few living players to embrace the special synergy between music emerging from Scotland and ideas imported from High Baroque Italy. Not out of an obsession with 18th century Scotland (though there would certainly be academic merit there…and it was a pretty cool place anyway), but because there was some good music played then and it’d be a shame to forget about it.

This also brings up my increasing problems with genre. I don’t envy the three judges—how are they supposed to rank seven convincing performances of modern traditional music? How are they possibly supposed to know where to put a convincing performance of Scottish-Baroque music in relation to the other seven? I’ve heard most of the other competitors either live or on recordings, and it seems that they held back some of their secret sauce in an effort to sound more “traditional”. I also received the strong impression from judges and audience members alike that I prevented myself from even being considered for a medal by not sounding “traditional” enough. But…what is “traditional”? Perhaps the best working definition I’ve come up with is “How most of the players of my grandfather’s generation in a given region sounded”, but that’s neither rigorous nor satisfying. If an obsession with traditionality leads to a restriction in time (e.g., discounting my 18th century style) or region (nobody at the competition played in a Highland style or Shetland style, despite those being as legitimately Scottish as the Northeast style that ruled the day) or repertoire (modern tunes are relatively uncommon at the Glenfiddich, and tunes by Skinner are disproportionately popular…to say nothing of the banned 16th century motets and 18th century sonatas and 21st century salsas that are arguably just as Scottish as the required jigs and reels), is it beneficial? Perhaps most importantly, what does it mean to play traditionally if nobody can agree on a definition of “traditional music”? If players at the jam sessions across the country I visited scoff at a competition for being “too traditional”, does that mean that they themselves are not traditional? But what else would you call a mixture of old and new music played in a regional style at pubs by non-professional musicians? If that’s not the very stereotype of traditional musicians, I don’t know what is. I don’t pretend to have answers for any of these questions, but they do trouble me. Perhaps my biggest concern is that such a focus on guarding the gates of “traditional music” will lead to arbitrary restrictions at the expense of musicality. But at the same time we must be careful of going too far the other direction, which leads either to a melting of styles into an indistinguishable mess or to the extinction of a worthy type of music. The via media is a narrow one, and ultimately I think we’re forced to put our faith in the good taste of artists and listeners.

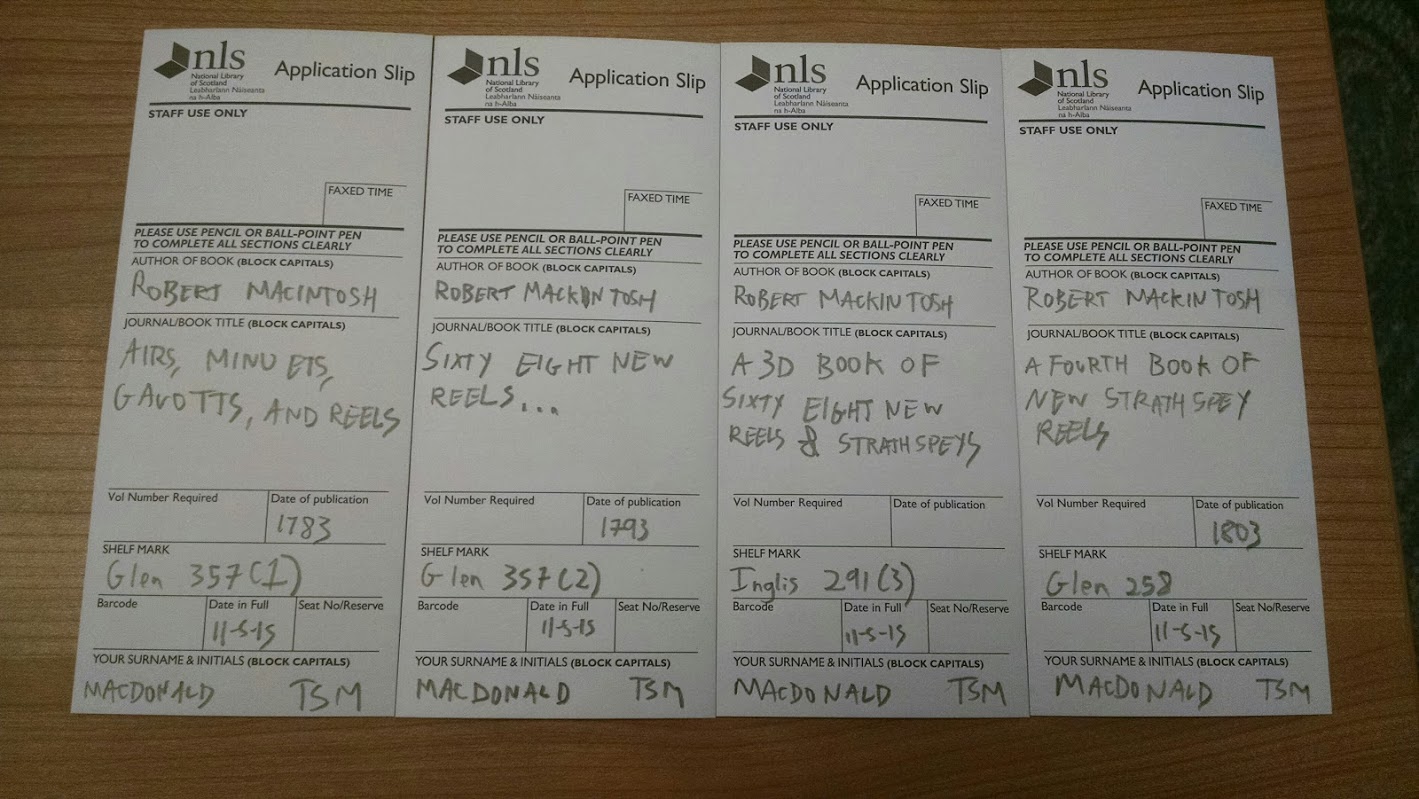

But this was meant to be a travel log, not a philosophical reflection. I’d be remiss not to thank Rachel and David for helping to prepare Jeremy and me before the trip and Ronnie, John, David, Aaron, Elizabeth, and Stuart for meeting with me during the two weeks I had post-Glenfiddich and saying fascinating things about the history of Scotland’s music (more on that once I’ve had a chance to digest it even more thoroughly!). It was a wonderful time bouncing around the country exploring new cities both as a musician and as a tourist and meeting these musical heavyweights. Thanks too to the traditional music school in Plockton (I believe the only high school dedicated to non-classical music in the world!) for hosting Jeremy and me for a workshop and concert. I also spent my fair share of time in the National Library of Scotland and John Purser’s private library making scans of literally thousands of pages of 18th (and a little 17th!) century sheet music. And still found time to see some wonderful museums, gorge on delicious food, and appreciate the beauty of downtown Edinburgh and the rural West Highlands and many places in between.

But perhaps more central to my Scottish music education than intellectual discussions about the life and work of William McGibbon or the accumulation of another 1740s music manuscript or whatever was the cultural education I also received. Seeing Niel Gow’s portrait and gravestone in person. Digging for potatoes on the Isle of Skye. Lying in the heather by the shore while John sang a Gaelic rowing song about the exact mountains and sea we were looking at. Peat fires. Single malt scotch. Wandering down the Edinburgh side street where Robert Mackintosh used to live. Feeding a highland cow out of my own hand. Hearing bitter rants about Gaelophobia and English colonialism. Having a pint in the pub while learning to play a new reel from a few fiddlers I just met. And making people’s feet tap, even when there’s a sign telling them not to. Because perhaps the most important thing about folk music is right there in its name: it straddles the abstract, impersonal world of music and the earthy, intimate world of folk like you and me.

Or as Robert Fergusson put it in the next stanza of “The Daft Days”:

For nought can cheer the heart sae weel

As can a canty Highland reel;

It even vivifies the heel

To skip and dance:

Lifeless is he wha canna feel

Its influence.